U bent hier

Nieuws (via RSS)

Beveiligingsmaatregel Windows via ongeldige handtekening te omzeilen

Advertorial: Cybersecurity trainen op een Cyber Range: zo doet KPN dat

Bibliotheek Rotterdam ondervindt nog steeds hinder van cyberaanval

Malafide Android-apps in Google Play Store 20 miljoen keer geïnstalleerd

Verbod op cashbetalingen boven 3.000 euro alleen uitvoerbaar met genoeg personeel

Implementation Imperatives for Article 17 CDSM Directive

COMMUNIA and Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte co-hosted the Filtered Futures conference on 19 September 2022 to discuss fundamental rights constraints of upload filters after the CJEU ruling on Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSMD). This blog post is based on the author’s contribution to the conference’s first session “Fragmentation or Harmonisation? The impact of the Judgement on National Implementations.” It first appeared on Kluwer Copyright Blog and is here published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0).

The adoption of the CDSM Directive marked several turning points in EU copyright law. Chief amongst them is the departure from the established liability exemption regime for online content-sharing service providers (OCSSPs), a type of platform that (at the time) was singled out from the broader category of information society service providers regulated for the last 20 years by the E-Commerce Directive. To address a very particular problem – the value gap – Article 17 of the CDSM Directive changed (arguably, after the ruling in (YouTube/Cyando, C-682/18) the scope of existing exclusive rights, introduced new obligations for OCSSPs, and provided a suite of safeguards to ensure that the (fundamental) rights of users would be respected. The attempt to square this triangle resulted in a monstrosity of a provision. In wise anticipation of the difficulties Member States would face in implementing, and OCSSPs in operationalizing Article 17, the provision itself foresees a series of stakeholder dialogues, which were held in 2019 and 2020. Simultaneously, the drama was building up with a challenge launched by the Republic of Poland against important parts of Article 17. Following the conclusion of all these processes, and while (some) Member States are considering reasonable ways to transpose Article 17 into their national laws, it is time to take stock and to look ahead. The ruling in Poland v Parliament and Council (C-401/19) is a good starting point for such an exercise.

Shortly after the CDSM Directive was adopted, the Republic of Poland sought to annul those parts of Article 17 which it argued, and the Court later confirmed, effectively require OCSSPs to prevent (i.e. filter and block) user uploads. Preventing control of user uploads constitutes, the Court confirmed, a limitation of the right to freedom of expression as protected under Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In its argumentation Poland suggested that it might not be possible to cut up Article 17, a provision of ten lengthy paragraphs. Indeed, the intricate relations between specific obligations, new liability structures and substantive and procedural user safeguards cannot be seen in isolation, and therefore require a global assessment. And this is what the Court embarked upon. Whilst assessing the constitutionality of Article 17, the Luxembourg judges, in passing, provided some valuable insights into how a fundamental rights compliant transposition might look, but also left crucial questions unanswered.

The Court was very clear that any implementation of Article 17 – as a whole – must respect the various fundamental rights that are affected. However, the judges in Luxembourg did not go into detail on how Member States should transpose the provision. Of course, it is part of the nature of directives that Member States have a certain margin of discretion how the objectives pursued by a directive will be achieved. To complicate matters, the Court stated expressly that the limitation on the exercise of the right to freedom of expression contained in Article 17 was formulated in a ‘sufficiently open’ way so as to keep pace with technological developments. Together with the intricate structure of Article 17 itself, this openness tasks Member States with a difficult exercise: to arrive at a transposition of Article 17 (and of course also other provisions of the CDSM Directive) that achieves the objective pursued while respecting the various fundamental rights affected (see Geiger/Jütte). The various national implementation processes have already demonstrated that opinions differ as to what constitutes a fundamental rights compliant implementation, and proposals have been made at different points of the spectrum between rightsholder-friendly and user-friendly transpositions.

The Court’s ruling makes a few, very important statements in this respect and thereby sets the guardrails beyond which national transpositions should not venture. First and foremost, control of user uploads must be strictly targeted at unlawful uses without affecting lawful uses. Recognizing that the employment of online filters is necessary to ensure the effective protection of intellectual property rights, the ruling highlights the various safeguards that ensure that the limitation of the right to freedom of expression is a proportionate one. Implicit here is that the targeted filtering of user uploads is a limitation of this fundamental right that necessitates six distinct measures that must be put in place, and which, in concert, ensure respect for the rights of users on OCSSP platforms.

Targeted FilteringTo limit the negative effects of overblocking and overzealous enforcement, any intervention by OCSSPs must be aimed at bringing the infringement to an end and should not interfere with the rights of other users to access information on such services. This suggests that it must be clear that only unlawful, or infringing content is targeted. The Court elaborates that within the context of Article 17 only filters which can adequately distinguish between lawful and unlawful content, without requiring OCSSPs to make a separate legal assessment, are appropriate. This is problematic, since copyright infringements are context sensitive, in particular in relation to potentially applicable exceptions and limitations. Requiring rightholders to obtain court-ordered injunctions before content can be subject to preventive filtering and blocking seems unreasonable, considering the amount of information uploaded onto online platforms. On the one side, copyright infringements are different from instances of defamation or other offensive speech, that was the subject of the preliminary reference in Glawischnig-Piesczek (C-18/18). On the other, the requirement of targeted filtering seems to eliminate the proposal made by the Commission in its Guidance (see Reda/Keller) to allow rightholders to earmark commercially sensitive content, which could be subject to preventive filtering for a certain limited amount of time. Unfortunately, the Court does not elaborate further how OCSSPs can target their interventions. It merely states that rightholders must provide OCSSPs with the relevant and necessary information on unlawful content, which failure to remove would trigger liability under Article 17(4) (b) and (c). What this information must contain remains unclear. Arguably, rightholders must make it very clear that certain uploads are indeed infringing.

User SafeguardsIn terms of substantive safeguards, Article 17 takes a frugal approach. To avoid speech being unduly limited, it requires Member States to ensure that certain copyright exceptions must be available to users of OCSSPs. These exceptions are already contained in Article 5 of the Information Society Directive as optional measures, but Article 17(7) makes them mandatory (see Jütte/Priora). Arguably not much changes with the introduction of existing exceptions (now in mandatory form). Moreover, the danger of context-insensitive automated filtering still persists, even though users enjoy these substantive rights.

Therefore, Article 17 foresees procedural safeguards, which is where the balance in Article 17 is struck. With the Court having confirmed that preventive filtering is an extreme limitation of freedom of expression, the importance of the procedural safeguards cannot be overstated (see Geiger/Jütte). The ruling in its relevant parts can be described as anticlimactic. Instead of describing how effective user safeguards must be designed, the judgment merely underlines that these safeguards must be implemented in a way that ensures a fair balance between fundamental rights. How such balance can be achieved was demonstrated in summer 2022, when the Digital Services Act (which is still to be formally adopted) took shape. A horizontally applicable regulation that amends the E-Commerce Directive, the DSA puts flesh to the bones that the CDSM Directive so clumsily constructed into a normative skeleton.

The DSA provides far more detailed procedural safeguards compared to the CDSM Directive. It is also lex posterior to the latter, which in itself is, however, lex generalis to the former. Their relation, but arguably also their genesis, holds the key to outlining not necessarily the solution to the CDSM conundrum, but to the questions that national legislators must ask.

The DSA sets out how hosting services and online platforms must react to notifications of unlawful content and how they must handle complaints internally; the DSA also outlines a system for out-of-court dispute settlement, which requires certification by an external institution. Some of these elements are, in embryonic form as mere abstract obligations, already contained in the CDSM Directive’s Article 17. And by definition, OCSSPs are hosting providers and online platforms in the parlance of the DSA, which is why these rules should also apply to them. OCSSPs, however, incur special obligations and are exempted from the general liability of the E-Commerce Directive and (soon) the DSA, because they are more disruptive – of the use of works and other subject matter protected by copyright and of the rights of users, the latter as a result of obligations incurred because of the former.

That some of the rules introduced by the DSA must also apply to OCSSPs has been argued elsewhere (see Quintais/Schwemer). It has been suggested that the rules of the DSA should apply in areas in which the DSA leaves Member States a margin of discretion or where the CDSM Directive is silent. CDSM rules that derogate from those of the DSA, specifically the absence of a liability exemption for user uploaded content will certainly remain unaffected. But there are good arguments to be made why in areas of overlapping scope, the DSA should prevail, or systematically supplement the CDSM Directive. Instead, the DSA rules must form the floor of safeguards that Member States have to provide, and which should be elevated in relation to the activities of OCSSPs. The reason is a shifting of balance between the fundamental rights concerns, which relates to the last paragraph of the CJEU’s ruling in Poland v Parliament and Council. The obligation to proactively participate in the enforcement of copyright intensifies the intervention of OCSSPs, as opposed to the merely reactive intervention required under the rules of the DSA. The effects for rightholders are beneficial (although the rationale for Article 17 suggests that it addresses a technological injustice) in the sense that OCSSPs must intervene in a higher volume of cases; the negative effects are borne by users of platforms, their rights are limited as a result. Arguably, this must be balanced by a higher level of protection of users, in this case in the form of stronger and more robust procedural safeguards. A further elevation of substantive safeguards would in itself not be helpful, since their enjoyment relies effectively on procedural support.

As a result, Member States should, or even must, consider that the elaboration of user safeguards in the form of internal complaints mechanisms and out-of-court dispute settlement mechanisms must find concrete expression in their national transpositions. They should be more robust than those provided by the DSA. Ideally, this robustness will be written into national laws and not left to be defined by OCSSPs as executors of the indecisiveness of legislators. The difficulty lies, of course, in the uncertainty of technological process, the development of user behaviour and the rise and fall of platforms and their business models. Admittedly, some sort of flexibility is necessary, the Court has recognized this explicitly. But if the guardrails that guarantee compliance with fundamental rights are not, and possibly cannot be written into the law, they must be determined by another independent institution. One institution, understood more broadly, could be the stakeholder dialogues required pursuant to Article 17(10) CDSM Directive. The Court listed them as one of the applicable safeguards, and a continuous dialogue between OCSSPs, rightholders and users could serve to define these guardrails more concretely. Such a trilogue, however, must take as its point of departure the ruling in C-401/19 and learn from the misguided first round of stakeholder dialogues. Another institution that could progressively develop standards for user safeguards are formal independent institutions, such as the Digital Service Coordinators (DSCs) required under the DSA. There, they have the task, amongst others, of certifying out-of-court dispute settlement institutions and awarding the status of trusted flaggers. Their tasks could also include general supervision and auditing of OCSSPs with regard to their obligations arising not only under the DSA, but also under the CDSM Directive. In the context of the Directive, DSCs could also be tasked with developing and supervising a framework for rightholders as ‘trusted flaggers’ on online content-sharing platforms. The role of DSCs under the DSA and their potential role in relation to OCSSPs is still unclear. But the reluctance of the legislature to give substance to safeguards and to clarify the relation between the DSA and the CDSM Directive mandates that the delicate task of reconciling the reasonable interests of rightholders and the equally important and vulnerable interest of users be managed by independent arbiters. Leaving this mitigation to platform-based complaint mechanism or independent dispute settlement institutions is an easy solution. A constitutionally sound approach would try to solve these fundamental conflicts at an earlier stage instead of making private operators the guardians of freedom of expression and other fundamental rights. While the Court of Justice of the European Union has not stated this expressly, its final reference to the importance of implementing and applying Article 17 in light of, and with respect to fundamental rights can be understood as a warning not to take the delegation of sovereign tasks too lightly.

The post Implementation Imperatives for Article 17 CDSM Directive appeared first on COMMUNIA Association.

Brits bouwbedrijf krijgt 5 miljoen euro boete voor datalek door phishingmail

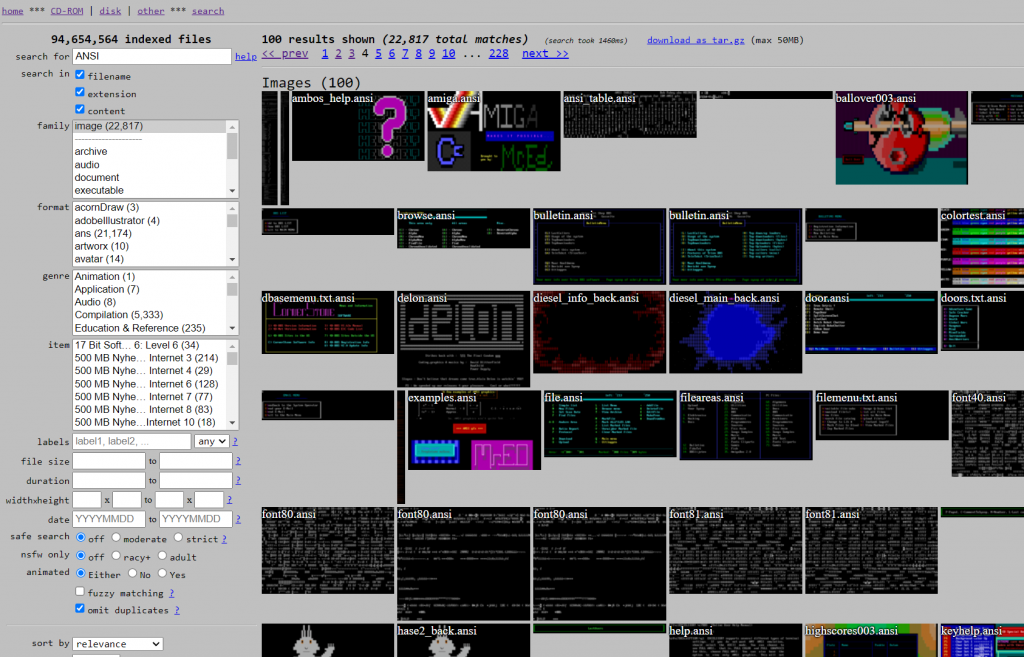

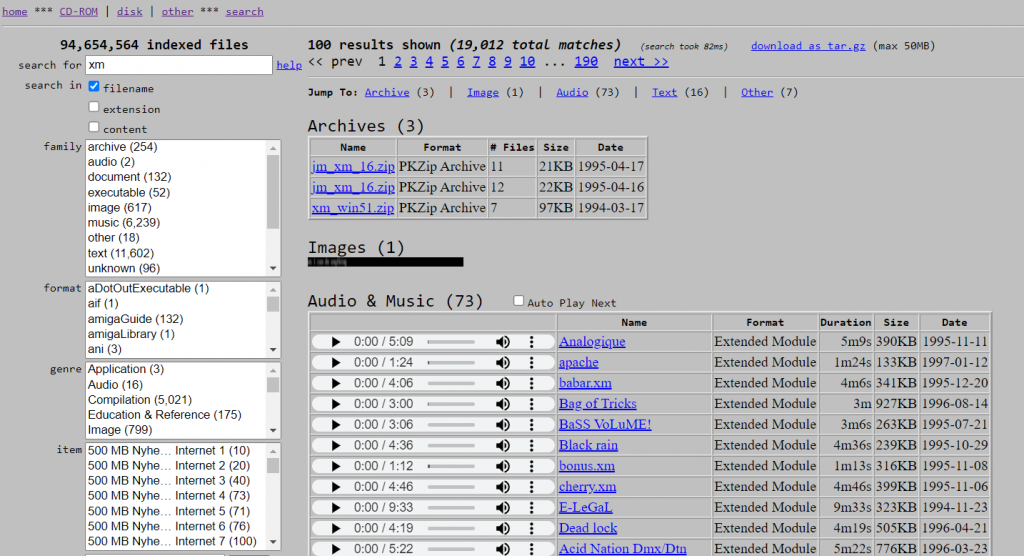

The Rise of DISCMASTER

A developer came to me a week ago with a project they’d been working on for over a year. The proposition of what they offered and the importance of what it would mean to historical software at Internet Archive was so compelling that within 48 hours, we’d announced it to the world.

The site is DISCMASTER.TEXTFILES.COM, and within its stacks lie multitudes of previously hidden software treasure, and a directed search engine that makes it a top-notch research tool.

More than a fascinating site, though, it represents some philosophies regarding the Archive’s stacks that are worth exploring as well.

The first thing that strikes a visitor to the site is either how strange, or how nostalgic it looks. The site is strikingly simple and references the first few years of the world wide web, when backgrounds were grey by default, and the width of the screen was almost always under 640 pixels. Same with the link colors, and use of (to the modern era) small icons next to the words and links. This is a version of the world wide web long gone.

However, underneath this simple exterior beats the heart of a powerful search engine and an astounding amount of processing that has analyzed millions of files to make them easy to interact with. If your area of research or interest is vintage/historical software, we’ve all been handed a top-class tool to discover long-lost files and bring them back instantly.

A Quick Reminder about CD-ROMs

From (very roughly) 1989 through to the early 2000s, CD-ROMs (and later DVD-ROMs) were one of the primary ways to transfer heaps of software or large-sized programs to end users. Instead of spending hours or literal days transferring software you may or may not have wanted after you received it, you could go to stores or on-line and purchase a plastic disc that contained between 600-700 megabytes of information on it.

The potential of this, in fact, was so strong, that there was an entire industry of providing databases, news summaries, and even all-digital magazines using this format. Booklets of CD-ROMs became resplendent, and libraries could allow patrons to check out these discs to do research with them.

Besides these more institutional compilations, an industry rose up of companies compiling software, artwork, music and more and selling them to end users. Companies with names like Walnut Creek, Wayzata, Valusoft, and Imagemagic would have catalogs of CD-ROMs to buy. Starting out with software from bulletin board systems and gathered from FTP sites, these CD-ROMs quickly ran out of easy-to-find material to fill, and an era of “shovelware” began, allowing these products to claim “thousands of files, gigabytes of materials” while pulling from more and more out-of-date sources.

As websites, torrents and other means of transport brought the era of physical media for software to a close, the world was left with a finite, contained pile of titles that had come out on CDs. And, as luck would have it, people have been uploading those out of date files to the Internet Archive for years.

The Final Piece

Therefore, sitting on the Archive, are tens of thousands of these CD-ROMs of the past. And for a very long time, it’s been possible to download a Disc image, analyze its contents, search for useful or potentially interesting items, and then find a way to make them work again.

That last piece, in fact, is the hardest – not just knowing where the files you’re looking for are located, but to be able to browse them without a massive host of helper applications scattered to the four winds. There are dozens of archive types, dozens and maybe hundreds of multimedia formats, and, even more frustrating, archives within archives – making everything that much harder to find.

DiscMaster has fixed this.

Within the search engine is the ability to find millions of files, categorized by type or size or date or extension, and then be presented them instantly. Three decades of computer software with layers upon layers of obfuscation are brought immediately to the top.

The developer wrote applications to grind through the contents of a CD-ROM and present them with previews that wouldn’t require anything but a browser to see. This can take hours to pull out of a single CD-ROM, but the results are breathtaking.

Audio and music files play in the browser. Flash, IFF, Bitmaps, Fonts and more display in preview. Macintosh, PC, Commodore, Atari and more are presented simply, without a mandate to track down the proper utility to figure out what they are.

In other words, vintage and historical software is back from the obfuscated darkness.

In the short time that Discmaster has been online, success stories are appearing. Authors are finding shareware programs they lost track of decades ago. Original versions of software that were thought impossible to track down just pop up in the search engine. And organizations dedicated to creating catalogs of now-dormant formats are suddenly handed a thousands-of-items to-do list on a silver platter.

The Philosophy of the Support Site

The ramifications and discoveries from Discmaster are going to be coming for a very long time – even if a researcher has a light memory of something they’re looking for, the search results will guide them in the right direction faster than ever before.

But beyond that, this site shows a different approach to the Internet Archive’s materials that’s worth seeing more of.

With over 100 petabytes of data, representing a mass of materials with all sorts of containers, metadata, and approaches by contributors, the Internet Archive has to be as general as possible. This generality extends to the presentation, search engine, and storage of the items.

It is a major effort to ensure the data stays secure, the metadata is searchable, and the ability to upload nearly anything results in a usable item details page.

But that’s kind of where it has to stop.

It’s asking an awful lot to both maintain an entity like this, and also design, say, a specifically-geared site for a relatively smaller set of people and needs. It can be done, but when energy and funding are limited, it’s sometimes best to stick to basics.

Discmaster shows one way it could be done. After working hard on its specific set (software from CD-ROMs), the entire site is constructed with its singular goal in mind. If it’s not obvious, the simple, almost-no-javascript and straightforward design lends itself to an entire family of browsers that run on those original machines. You’ll be able to download Amiga software through your Amiga, your Atari software to your Atari and so on. A thousand little touches and flourishes live easily on this custom experience – because it has the freedom to allow them.

Perhaps seeing Discmaster in action will encourage others to interact with the Internet Archive as a pool, a container of resources that could receive some of the powerful analysis along specific lines. If they can then be fed back to the Archive at the end, even better; but let a hundred supporting sites bloom.

Meanwhile, enjoy the history of software – it just got a lot easier to find.

The post The Rise of DISCMASTER appeared first on Internet Archive Blogs.

Banken noemen waarschuwing Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens teleurstellend

Tor Project eist end-to-end encryptie voor privéberichten op alle platforms

FBI waarschuwt ziekenhuizen voor ransomware-aanvallen via vpn-servers

Community Turns Out to Celebrate Promise of Democracy’s Library

Friends and supporters of the Internet Archive gathered October 19 at the organization’s headquarters in San Francisco to celebrate the launch of Democracy’s Library.

Plans to collect government documents from around the world and make them easily accessible online were met with enthusiasm and endorsements. Speakers at the event expressed an urgency to preserve the public record, make valuable research discoverable, and keep the citizenry informed—all potential benefits of Democracy’s Library.

“If we really succeed — and we have to succeed — then Democracy’s Library might become an inspiration for openness in areas that are becoming more and more closed,” said Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle.

The 10-year project aims to make freely available the massive volume of government publications (from the U.S. and other democracies), including books, guides, reports, surveys, laws and academic research results, which are all funded with taxpayer money, but often difficult to find.

To kick off the project, Kahle announced the Internet Archive’s initial contributions to Democracy’s Library:

- United States .gov websites collected since 2008;

- Crawls of the U.S. state government websites;

- Digitized microfilm and microfiche from the U.S. Government Publishing Office, NASA and other government entities;

- Crawls of government domains from 200 other countries;

- 50 million government PDF documents made into text searchable information.

It will be a collaborative effort, said Kahle, calling upon others to join in the ambitious undertaking to contribute to the online collection.

The need for Democracy’s Library“We need Democracy’s Library. The Internet Archive’s work leading this project represents a critical step in the evolution of democracy,” said Jamie Joyce, executive director of The Society Library and emcee of the program. “Archives and libraries, as they’ve always done in the past, will continue to change in their scope, scale, and capabilities to be of critical use to society, especially democratic societies. Tonight is about witnessing another transformation.”

Although there is more data available than ever before, Joyce said, society’s knowledge management system is badly broken. Misinformation is rampant, while high quality government data is buried and scattered across different federal, state and local agencies.

Having public material consolidated, digitized and machine readable will allow journalists, activists, and others to be better informed. It will also make democracy more transparent and accountable, as well as protect the historical documents. “We will not be able to compute in the future what we do not save today,” Joyce said.

At a time when polarized politics can put information at risk, the event highlighted the need to safeguard public data.

Gretchen Gehrke, co-founder of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative, has been working in partnership with the Internet Archive to track changes in federal environmental websites.

“People should be able to know about environmental issues and have a say in environmental decisions,” she said. “For the last 20 years, the majority of this information has been delivered through the web, but the right to access that information through the web is not protected.”

Gehrke described how public resources and tools related to the federal Clean Power Plan, a hallmark environmental regulation of the Obama administration, were taken down from the Environmental Protection Agency’s website under President Trump’s tenure.

“There are no policies protecting federal website information from suppression or outright censorship,” Gehrke said. “This case serves as an example of why we need Democracy’s Library to preserve and provide continued access to these critical government documents.”

When statistics are being cited in policy debates, citizens need to be able to have access to sources of claims. For example, Sharon Hammond, chief operating officer of The Society Library, said documents related to the environmental impact of California’s Diablo Canyon power plant should be easily available. There are nearly 5 different government bodies that have some role in monitoring the plant’s ecological impact, but the agencies house the reports on their own websites.

“Finding governmental records about public policy matters should not be a barrier to becoming an informed participant in these collective decisions,” Hammond said. “When we connect evidence directly to the claims and make that information publicly accessible as a resource, we can improve the public discourse.”

Hammond said a searchable, machine readable repository of government documents, with active links and a register of relevant government agencies, will dramatically increase meaningful access to the public’s information.

An international visionThe effort is an international one, and Canada has stepped forward as an early partner.

Canada has contributed crawls by the Library and Archives Canada of all the country’s government websites, as well as digitized microfilm and books from the Canadian Research Knowledge Network, Canadiana, and the University of Toronto.

Leslie Weir, librarian and archivist of Canada, spoke in support of the initiative.

“We know by making our collection and work of government openly accessible, we will create a more engaged community, a community that participates in elections, school board meetings, in public consultations, and yes, even and especially in protests,” Weir said. “Access is the key to understanding. And understanding is the underpinning of democracy.”

Celebrating heroesThe festivities concluded with a tribute to Carl Malamud, recipient of the 2022 Internet Archive Hero Award. Corynne McSherry, legal director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, presented the award. “Carl has always seen what the internet could be. He has dedicated his life to building that internet,” she said. “He is a true hero.”

Malamud said government information is more than just a good idea. “It is about the law. It is about our rulebook. It is the manual on how we, as citizens, choose to run our society. We own this manual,” he said. “We cannot honor our obligations to future generations if we cannot freely read and speak and even change that rulebook.”

Malamud urged the audience to get involved to realize the vision of Democracy’s Library and guarantee universal access to human knowledge.

“This is our moment. We must build a distributed and interoperable internet for our global village. We must make the increase in diffusion of knowledge our mutual and everlasting mission,” Malamud said. “We must seize the means of computation and share their fruits with all the people. Let us all swim together in the ocean of knowledge.”

For more on Malamud’s career and contributions, read his profile here.

The post Community Turns Out to Celebrate Promise of Democracy’s Library appeared first on Internet Archive Blogs.

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102617_0.jpg?itok=OJkkWhxY)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102628.jpg?itok=CUvhRRr7)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen] - Opnemen en onderhouden](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102418.jpg?itok=d7rnOhhK)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102433.jpg?itok=CgS8R6cS)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102445_0.jpg?itok=4oJ07yFZ)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102500.jpg?itok=ExHJRjAO)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102524.jpg?itok=IeHaYl_M)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud bronnen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20bronnen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102534.jpg?itok=cdKP4u3I)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud thema's en rubrieken]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20themas%20en%20rubrieken%5D%2020-9-2009%20185626.jpg?itok=zM5uJ2Sf)

![Reference manager - [Raadplegen aantekeningen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BRaadplegen%20aantekeningen%5D%2020-9-2009%20185612.jpg?itok=RnX2qguF)

![Reference manager - [Relatie termen (thesaurus)]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BRelatie%20termen%20%28thesaurus%29%5D%2014-2-2010%20102751.jpg?itok=SmxubGMD)

![Reference manager - [Thesaurus raadplegen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BThesaurus%20raadplegen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102732.jpg?itok=FWvNcckL)

![Reference manager - [Zoek thema en rubrieken]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BZoek%20thema%20en%20rubrieken%5D%2020-9-2009%20185546.jpg?itok=6sUOZbvL)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud rubrieken]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%2020-9-2009%20185634.jpg?itok=oZ8RFfVI)

![Reference manager - [Onderhoud aantekeningen]](https://www.labyrinth.rienkjonker.nl/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/Reference%20manager%20v3%20-%20%5BOnderhoud%20aantekeningen%5D%2014-2-2010%20102603.jpg?itok=XMMJmuWz)